The Chemistry Behind Freshness: Why Produce Spoils and How We Fight It

- Gil Refael, Ph.D (ABD)

- Nov 30, 2025

- 3 min read

Updated: Dec 1, 2025

Ever wondered why your strawberries lose their punch or why avocados brown so quickly? The answer lies in the hidden chemistry of fruits and vegetables.

Gil Refael, Ph.D (ABD) | Senior Formulation Researcher

From the moment produce is harvested, a cascade of molecular changes begins, affecting taste, texture, aroma, and shelf life. Let’s explore the key chemical processes behind spoilage and how LiVA helps maintain freshness without chemicals.

The Journey Begins at Harvest

Harvesting marks the beginning of a fruit’s transformation. Mechanical stress - cutting, sorting, chilling - damages cells and exposes sensitive molecules to oxygen. This triggers a chain of chemical reactions that degrade flavor, color, and texture. Even gentle handling cannot prevent it altogether.

Oxidation: The Fast-Forward Button to Decay

Oxidation is a radical chain reaction where reactive molecules (such as lipids) lose electrons to oxygen, forming unstable free radicals. These radicals damage other molecules, leading to rancidity, browning, and nutrient loss. The reaction is self-propagating and only stops when radicals neutralize each other.

Antioxidants: Nature’s Defenders

Antioxidants like polyphenols and vitamin C protect cells by neutralizing radicals. But once exposed to air, they degrade quickly. This loss accelerates spoilage, especially in lipid-rich produce like berries or avocados. In smoothies or juices, blending increases exposure to oxygen, causing rapid flavor and nutrient loss.

Enzymes: Accelerators of Spoilage

Enzymes like Polyphenol Oxidase (PPO) and Lipoxidase speed up oxidation. PPO turns antioxidants into brown pigments (think apple slices), while Lipoxidase breaks down fats, creating off-flavors. Heat, oxygen, and tissue damage amplify these effects.

Ethylene: The Ripening Hormone

Ethylene gas signals ripening, but can also accelerate spoilage - especially in cut or shredded produce. It’s like pressing fast-forward on the fruit’s life cycle.

Vitamins, Pectin & Cell Walls

Vitamin C degrades quickly after cutting. Pectin and cellulose break down, softening texture. These changes make produce look and taste “tired” even before microbial spoilage sets in.

Chemical Meets Microbial

Chemical spoilage can make tissues more vulnerable to microbes, and microbial enzymes can worsen chemical degradation. This synergy explains how microbiome management - like LiVA’s approach - can influence fruit chemistry.

LiVA®: Preserving Chemistry Naturally

Unlike synthetic preservatives, LiVA works by supporting the fruit’s natural microbiome. This helps maintain the integrity of antioxidants, enzymes, and cell structures - slowing spoilage without disrupting the fruit’s native chemistry. By avoiding chemical additives, LiVA allows produce to retain its original molecular balance, flavor, and nutritional values - naturally.

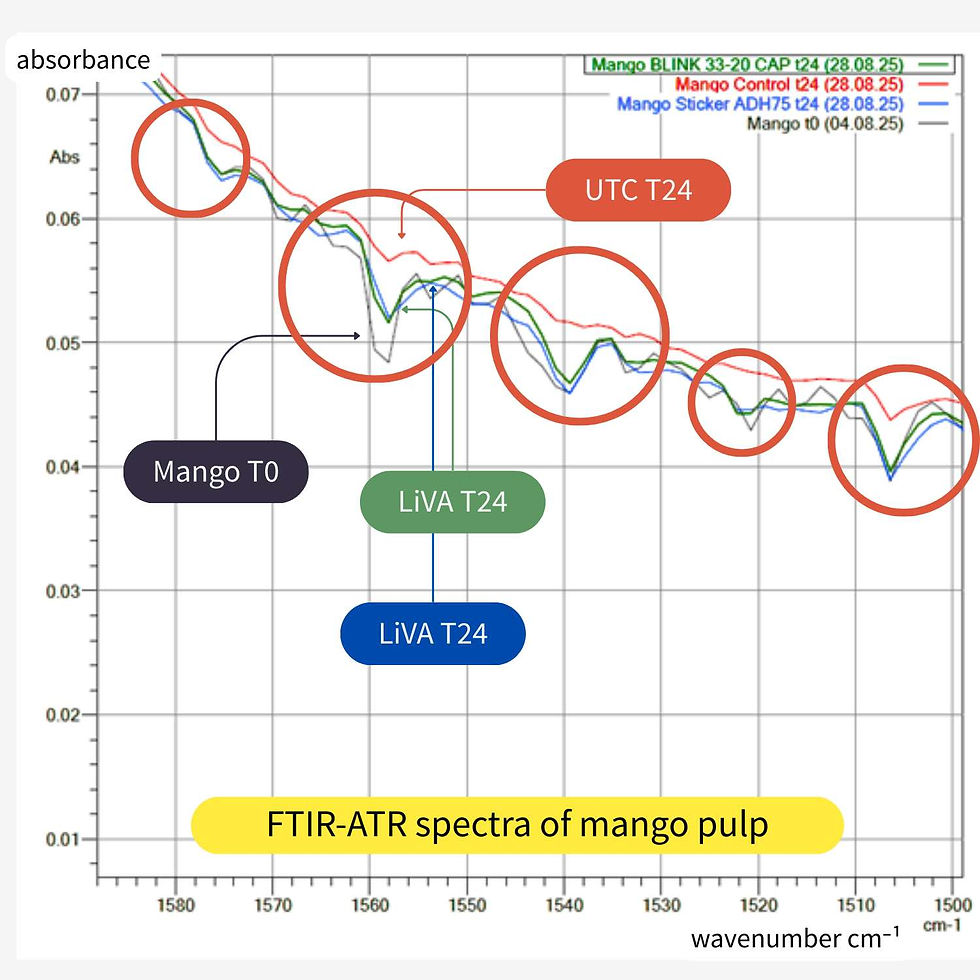

The mango’s inner flesh was blended and analysed for its infrared (IR) absorbance across a broad spectral range. In the region between 1500 and 1580 cm⁻¹, distinct differences were observed — notably, four peaks associated with aromatic or antioxidant molecules. These characteristic peaks, clearly visible in fresh mango, disappeared after 24 days of storage at 8 °C in the untreated control samples. In contrast, they remained stable in LiVA-treated mangoes, closely resembling the profile of freshly harvested fruit.

This provides evidence that LiVA treatment influences not only the fruit’s microbiome but also its internal chemistry — and, ultimately, its flavor.

The Takeaway

Chemical spoilage is a powerful force shaping the shelf life and quality of fresh produce. From enzymatic browning to vitamin loss and lipid oxidation, these reactions start the moment a fruit is harvested – and continue until it reaches your plate.

For anyone in the food industry, understanding this chemistry is not merely academic, but key to preserving flavour, nutrition, and consumer trust.

By understanding how molecules behave under stress and how to control those reactions, we can keep produce fresher, longer, and closer to the vibrant quality nature intended.

Bibliography:

De Corato, U. (2020). Improving the shelf-life and quality of fresh and minimally-processed fruits and vegetables for a modern food industry: A comprehensive critical review from the traditional technologies into the most promising advancements. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 60(6), 940-975.

Galani, J. H., Patel, J. S., Patel, N. J., & Talati, J. G. (2017). Storage of fruits and vegetables in refrigerator increases their phenolic acids but decreases the total phenolics, anthocyanins and vitamin C with subsequent loss of their antioxidant capacity. Antioxidants, 6(3), 59.

Geng, L., Liu, K., & Zhang, H. (2023). Lipid oxidation in foods and its implications on proteins. Frontiers in Nutrition, 10, 1192199.

Scalzo, J., Mezzetti, B., & Battino, M. (2005). Total antioxidant capacity evaluation: critical steps for assaying berry antioxidant features. Biofactors, 23(4).

Skrovankova, S., Sumczynski, D., Mlcek, J., Jurikova, T., & Sochor, J. (2015). Bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity in different types of berries. International journal of molecular sciences, 16(10), 24673-24706.